Glenn Roberts and The Genesis of The Jump Shot

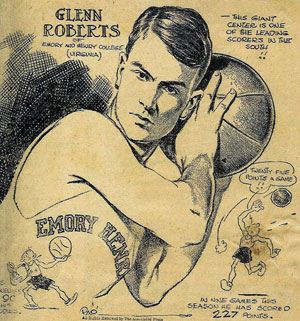

Early cage star led the nation in scoring at tiny Emory & Henry College with his revolutionary new shooting style.

Glenn Roberts was born October 25, 1912 on a hillside farm in Pound, Virginia, a small rural town of 150 inhabitants in Wise County near the southwest corner of the Old Dominion State. The Roberts family, nine strong, eked out a living in tiny Pound where life was always harsh.

Glenn Roberts was born October 25, 1912 on a hillside farm in Pound, Virginia, a small rural town of 150 inhabitants in Wise County near the southwest corner of the Old Dominion State. The Roberts family, nine strong, eked out a living in tiny Pound where life was always harsh.

How harsh?

Glenn and his brothers cleared the white stuff out of every room in the old farmhouse most mornings after a snowfall.

Glenn and his brothers walked to school. Rain or shine the old dirt road was five miles one way and Glenn regularly made the trek by the light of his lantern when the dark of the evening sky came early each fall.

This was life in Pound for the Roberts boys. Humble to say the least.

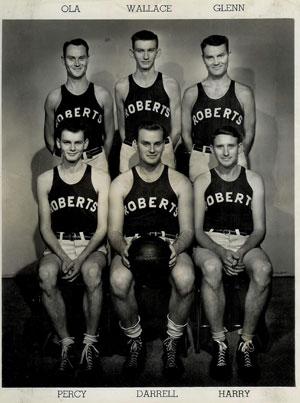

Glenn was the second oldest of the seven boys – Guy, Glenn, Harry, Ola, Darrell, Percy and Wallace in order – in the Roberts household and he more than held his own in any physical endeavor. The Roberts boys were all strapping young lads, perhaps the result of years spent working on the family farm. Still Glenn and his brothers found time for other diversions and basketball was always a favorite. “For us it was basketball, farm chores, and school,” Glenn recalled. Unwinding after a long day or occasionally before the school bell rang usually meant basketball, played on a makeshift outdoor basketball court. There Glenn experimented with a new style of shooting. Today, we know this shot as the jump shot.

“Our high school did not have an indoor basketball court when I was playing. Because of our eagerness for basketball we practiced in all kinds of weather. At times it was too muddy to dribble the ball and move effectively especially since we practiced most of the time in our pair of all-purpose shoes. When we could avail ourselves of a basketball we would often congregate under our basket and practice in an unorganized way. Whoever recovered the ball after a shot was attempted was on his own to get off a shot at the basket against the combined efforts of everyone else to prevent the shot from being taken. Because of this combination of conditions it was necessary to devise something besides an ordinary effort to even get the ball to the basket unless you got lucky. By starting to jump as high in the air as I could after recovering the ball and releasing the ball after jumping out of reach of the others I started to get the ball to the basket consistently and before long I even succeeded in making some baskets without depending entirely on luck.”

The old saying goes that necessity is the mother of invention. In the case of Glenn Roberts, a practical solution to an old problem signaled the future of basketball. Glenn refined his new shooting style in high school and by the time he graduated he had led Christopher Gist High School to two state championships and one undefeated season going 35-0 in 1931. The two-time All-State performer was off to college in the fall to rerewrite the record books at Emory & Henry College.

The Roberts boys were all great players but Glenn was the king of the court. Still five of Glenn's six brothers played on state championship teams in high school.

![]()

Emory & Henry College, with a 400-strong student body during the era of Glenn Roberts, stretches over 330 acres in the village of Emory, Virginia, in the Virginia highlands. Evoking the spirit of Thomas Jefferson, Emory and Henry, a Methodist school, seeks to enlighten and nurture its students in an environment of physical beauty and intellectual challenge.

Emory & Henry College, with a 400-strong student body during the era of Glenn Roberts, stretches over 330 acres in the village of Emory, Virginia, in the Virginia highlands. Evoking the spirit of Thomas Jefferson, Emory and Henry, a Methodist school, seeks to enlighten and nurture its students in an environment of physical beauty and intellectual challenge.

But even better than all that for Glenn Roberts – tiny Emory had an indoor gymnasium. Glenn had waited almost 20 years to play on an indoor homecourt and it was in that gymnasium that Roberts perfected his new shot.

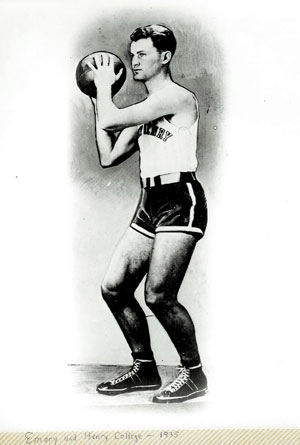

From 1931 to 1935, Roberts played pivot for the Emory & Henry College Wasps putting up numbers that most college players still do not match to this day. Roberts scored at will, tallying 2,013 points in 104 games over the course of his college career, an average of 19.4 points per contest. In one game against Union College of Kentucky, Roberts tallied 38 points. In another game against the House of David, a professional barnstorming team of the era, Roberts netted 50 points...against a 7-foot opposing center! At one point during the 1933 season, Roberts had scored twice as many points as his nearest conference competitor. And while the schedule included only teams located east of the Mississippi River, Emory & Henry took on all comers. Big schools like Tennessee and Virginia Tech and of course the smaller schools like the aforementioned Union College. Glenn scored 1,531 career points, a national record at the time, against college teams. He put up 482 points against professional, semi-professional, and YMCA teams. These numbers let basketball insiders know that the jump shot was the real deal. Newspaper scribes compared him to the likes of Joe Lapchick and Dutch Dehnert, two of the greatest players in basketball’s first half-century.

Despite his solid frame – Roberts stood 6’4” and weighed 180 pounds – Glenn was nicknamed “Slim” and certainly benefited from the tutelage of his 5’5” coach, “Pedie” Jackson. Jackson worked with Roberts on playing the pivot position with his back to the basket. Other players would pass to him, Roberts would leap into the air, turn, and shoot the ball with some “English” so that it would hit the backboard with spin and drop through the basket. Glenn operated down low in games and scored most of his points on jump shots from 5 feet in.

“...it was in college that I became proficient in developing multiple moves such as the forward and backward pivot and dribble to maneuver into a better shooting position. It was also in college that my timing developed to the point where I could jump and absorb the shock from the defensive effort and then hang free in the air momentarily (sic) before releasing the ball. As a result I could make a basket almost every time I got the ball within the present highpoint distance from the basket.”

Recognized as one of the greatest players in the country, Roberts was named All-State and All-Conference center all four years at Emory, the last by unanimous vote.

He was a First Team Helms Foundation All-America in 1935, an honor made all the more amazing by the fact that the other four members of that year's squad - Leroy Edwards of Kentucky, Bud Browning of Oklahoma, Pitt's Claire Cribbs and Jack Gray of Texas - played at bigger schools where media coverage was more mainstream.

Roberts became something of a celebrity in his own right though as he was even featured in Ripley’s Believe It Or Not. But perhaps the greatest testimony to his scoring feats occurred when members of the Rules Committee began efforts to diminish the advantage of the big man by instituting the three-second rule.

Glenn Roberts graduated from Emory & Henry College in 1935. He was a well-rounded student-athlete earning varsity letters in basketball and making the Honor Roll all four years. In his sophomore year Glenn served as the Vice-President of the Student Body and he was a member of the Beta Lambda Zeta fraternity. The scoring records he set at Emory & Henry made for headlines all over the country. Soon Stanford’s Hank Luisetti, another shooting prodigy, would begin his assault on the Glenn Roberts’ book of scoring records but that was of little concern for the Emory & Henry graduate who needed work in a down economy.

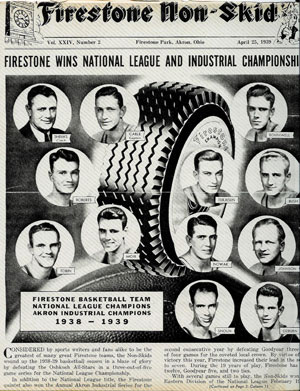

The 1930s were the trying years of the Great Depression. With jobs difficult to come by, Glenn Roberts declined numerous offers to play basketball professionally and opted instead to teach and coach girls basketball at Norton High School in Norton, Virginia. His teams won the district championship the two years he coached, 1936 and 1937. But when he was offered an opportunity to play basketball – and work a steady job – for the Akron Firestone Non-Skids of the National Basketball League, the package deal was too good to turn down. Boasting five All-Americas in its lineup, Akron was touted as one of the best and strongest teams in the country according to news reports at the time. The NBL itself listed fifteen All-Americas, including John Wooden of Purdue, and was considered one of the top leagues in the country. The NBL was later absorbed by the Basketball Association of America and in 1949 the two leagues became the NBA.

Roberts played for one season with Firestone and helped the team to the 1939 NBL Eastern Division championship with a 24-3 record and the NBL Championship by besting the powerhouse Western Division champions, the Oshkosh All-Stars, three games to two, an experience Roberts would later call “the greatest thrill.” The Firestone lineup was stacked with former All-Americas including Paul Nowak and John Moir, both standouts at Notre Dame in the mid-1930s.

While still passionate about basketball, the recently married Roberts sensed that it was not going to provide him with a career so he took full advantage of the job opportunity with Firestone after his one memorable season. Still basketball remained an important piece of his life. During the early 1940s, Roberts and five of his brothers formed an all-family team that dominated the Northeast Ohio industrial leagues. Taking a leave of absence from Firestone in January 1945, Roberts and his brothers barnstormed Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and West Virginia, playing colleges, professional, and semi-professional teams, to sell war bonds. On March 10, 1945 the Roberts five played a speedy Navy V-12 quintet from Virginia representing Milligan College. Before a capacity crowd in Norton, VA, the Roberts brother act defeated the sailors 36 to 33 and raised $50,000 from war bond sales.

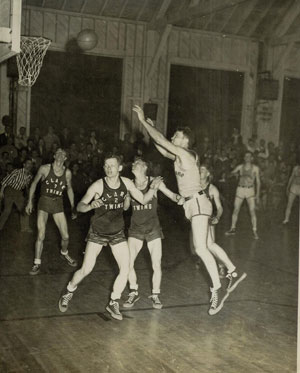

The Roberts clan also competed in an annual hardwood event touted as the National Family Basketball Tournament. First played on the campus of Atlantic Christian College in Wilson, North Carolina in 1943, it was one of the most unique, if not strangest, events in basketball history. The tournament field consisted of as many as sixteen teams each comprised of members of a single family. Men, women, and children competed and with no age limit there were teams that included moms, dads, grandparents, and grandchildren! The Roberts quintet made it to the tournament finals twice, losing both times in 1947 and 1949 to the same family team, the Clarks, from Huntington, Indiana. The Clarks were younger and played fairly regularly in local circles and the better conditioned athletes won out. Still the Roberts family was no pushover when basketball was on the agenda. The family tournament was suspended in 1951 because many of the competing families had members serving in the armed forces during the Korean War.

The Roberts clan also competed in an annual hardwood event touted as the National Family Basketball Tournament. First played on the campus of Atlantic Christian College in Wilson, North Carolina in 1943, it was one of the most unique, if not strangest, events in basketball history. The tournament field consisted of as many as sixteen teams each comprised of members of a single family. Men, women, and children competed and with no age limit there were teams that included moms, dads, grandparents, and grandchildren! The Roberts quintet made it to the tournament finals twice, losing both times in 1947 and 1949 to the same family team, the Clarks, from Huntington, Indiana. The Clarks were younger and played fairly regularly in local circles and the better conditioned athletes won out. Still the Roberts family was no pushover when basketball was on the agenda. The family tournament was suspended in 1951 because many of the competing families had members serving in the armed forces during the Korean War.

Glenn and his brothers would go on to build up a thriving tire recapping business in and around Pound. Glenn eventually left Firestone in 1964 returning home to Virginia where his oldest son, Glenn, Jr., was flourishing with his own Firestone dealership. The game never left Glenn as he coached two seasons at Clinch Valley College of the University of Virginia turning a program that won only two games in the previous season into a winner, going 14-6 both seasons. At the time of Glenn Roberts’ death in 1980, he left behind a business he ran with his sons, Glenn Jr. and Larry, that expanded from Virginia into Kentucky and Tennessee. And of course, the legacy of the two-handed jump shot.

![]()

Today the jump shot is a common way to score away from the basket. Players shoot fade-away jumpers, off-balance jumpers, baseline jumpers, turnaround jumpers, jumpers off screens - all with pinpoint accuracy. But until Glenn Roberts laced em up, basketball was mostly a patterned affair with a pass-pass-pass-open set shot approach. His career preceded the elimination of the center jump rule, making his scoring exploits all the more remarkable. In an era of slow, low-scoring, methodical games, Roberts’ innovation changed the landscape of the sport. There is of course no absolute proof that Glenn Roberts was the first person to shoot the jump shot. He was simply the first to use the new shot to reach such high-scoring exploits. Hitting for nearly 20 points per game in an era when teams rarely exceeded 20 was nothing short of brilliant. Glenn Roberts was a pioneer and his contribution to the game reverberates to this day.